Summary

Answer: when you run afoul of IRC §7874.

IRC §7874 was designed to stop you from reincorporating your U.S. publicly-traded multinational in, say, Bermuda. But it will apply equally to a nonresident doing normal estate tax planning for very ordinary U.S. real estate.

Nonresidents often put U.S. real estate in corporate structures to prevent estate tax exposure. A foreign corporation is at the top of the structure, and the nonresident individual owns the shares of stock of the foreign corporation.

Done right, it works: no U.S. estate tax is imposed on the value of the U.S. real estate holdings in the structure. Done wrong, estate tax exposure remains. IRC §7874 is the reason why.

Income tax – IRC §897 – let’s cheerfully ignore this

There are two Federal tax concerns you will think about restructuring the real estate ownership. One is income tax. IRC §897(a) makes any transfer of U.S. real estate by a nonresident into a gain recognition event until proven otherwise.

I am cheerfully ignoring income tax considerations. Let’s make up some facts that allow us to do this: adjusted basis for the real estate equals its fair market value.

Whether you can engineer this into a nonrecognition event (think IRC §351) or IRC §897 makes it into a gain recognition event, you don’t care. It’s all just tax paperwork, without any capital gain tax to pay.

In real life, you really do care about capital gains tax. Amongst friends, we can assume a spherical cow. Let’s ignore capital gains tax.

Estate tax risk of direct ownership

Direct ownership of U.S. real estate by a nonresident-noncitizen of the United States is a bad idea.

If the individual nonresident-noncitizen owner dies, estate tax is payable. The house is an asset included in the gross estate. IRC §2103 says that a nonresident-noncitizen decedent’s gross estate includes only assets “situated in the United States” and nothing is more certain to be located in the United States than real estate within its borders.

And the unified credit for nonresident-noncitizens is puny. A nonresident-noncitizen decedent’s estate is allowed a unified credit of $13,000. IRC §2102(b)(1). This exempts a princely $60,000 of assets from estate tax.

U.S. citizens and residents have a massive unified credit, which exempts $12,900,000 of assets (deaths in 2023) from estate tax. IRC §2010.

As a result, estate tax liability is a problem for almost every nonresident-noncitizen with real estate holdings in the United States. (Where is the sub-$60,000 real estate to be found? And who will buy it?)

You can’t owe estate tax if your gross estate is zero

You don’t have an estate tax problem if you don’t own anything when you die. Or to put it in technical terms, if a decedent’s gross estate is zero, estate tax must be zero. This concept applies equally to nonresident-noncitizens as it does to U.S. citizens and residents.

- A nonresident’s gross estate is defined in IRC §2103. It includes only assets situated in the United States.

- Gross estate minus various stuff equals the taxable estate. IRC §2106.

- Taxable estate times tax rate equals estate tax. IRC §2101.

If the decedent’s gross estate is zero (meaning all of the decedent’s assets are outside the United States), then:

- $0 gross estate.

- $0 (minus any or no deductions, it doesn’t matter) equals $0 taxable estate.

- $0 taxable estate multiplied by the estate tax rate equals $0 estate tax.

How to achieve a $0 gross estate

The nonresident-noncitizen’s gross estate includes only property situated in the United States. IRC §2103 says (emphasis added):

For the purpose of the tax imposed by section 2101, the value of the gross estate of every decedent nonresident not a citizen of the United States shall be that part of his gross estate (determined as provided in section 2031) which at the time of his death is situated in the United States.

U.S. real estate is self-evidently located in the United States.

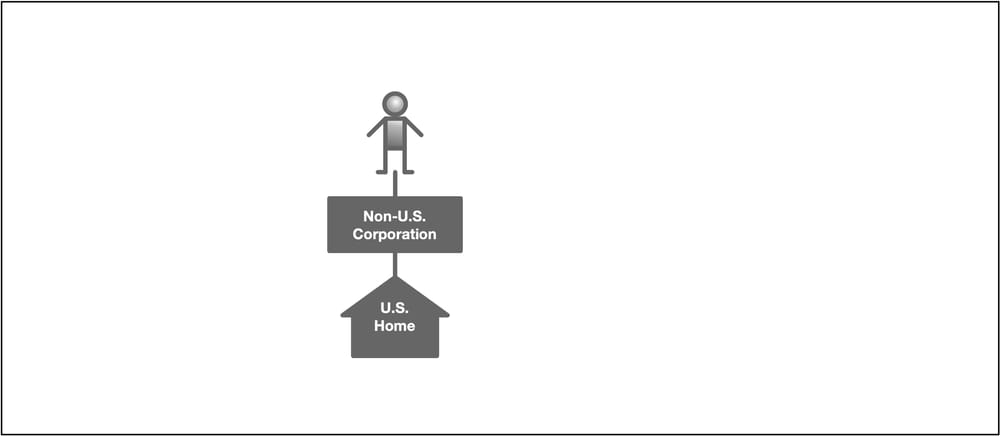

A share of stock of a foreign corporation is located in the country of the corporation’s formation. You own stock of a Bahamas corporation? That asset (the share of stock) is located in the Bahamas for U.S. estate tax purposes. IRC §2104(a) says:

For purposes of this subchapter shares of stock owned and held by a nonresident not a citizen of the United States shall be deemed property within the United States only if issued by a domestic corporation.

The thought immediately occurs to you: let’s have a non-U.S. corporation own the U.S. real estate.

And you’re right. That eliminates the estate tax problem because the only thing in the decedent nonresident-noncitizen’s gross estate is stock of a foreign corporation, which is situated outside the United States.

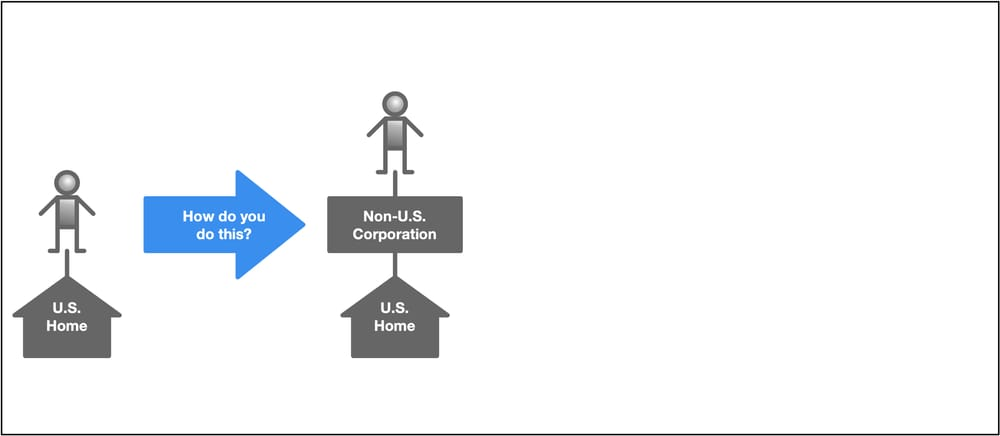

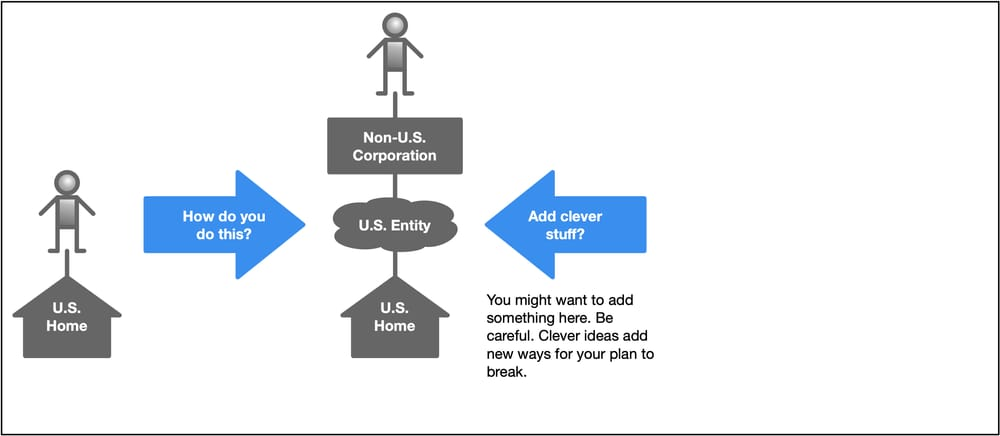

But how do you get from here to there?

“There’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip.”

If the individual already owns the real estate directly, how do you set up the transfer so you don’t destroy the estate tax advantage that you seek?

How you get to the destination is as important as the destination itself. Just think, for instance, of corporate reorganizations. Your corporate reorg might end up with the desired structure. But did you get the desired tax result? Done right, a corporate reorganization is a nonrecognition event. Done wrong, your reorganization manufactured accidental income.

Same same estate tax. Done right, you get the estate tax protection you want. Done wrong, you don’t – even when you end up with the intended holding structure.

“Done right” is easy. A simple grant deed will do the trick. Nonresident-noncitizen owner of the U.S. real estate records a grant deed transferring ownership of the real estate to the foreign corporation.

Done.

The nonresident-noncitizen, who will someday attain decedent status, owns shares of stock of a foreign corporation. The shares of stock of the foreign corporation are located outside the United States.

Therefore, the nonresident-noncitizen decedent’s gross estate has nothing in it. There’s nothing to tax, so the tax payable is nothing.

But what if you want to add a dose of clever?

But maybe you don’t want the foreign corporation to own the U.S. real estate directly. I certainly don’t like this – for practical reasons.

- Maybe you’re thinking about dealing with the future sale and FIRPTA withholding.

- Maybe you are thinking of the future sale and dealing with real estate professionals who might never have seen a foreign corporation before. How do you prove to a skeptical closing agent that your corporation in Burkina Faso exists and is in good standing, for instance? Why add gratuitous friction to your life?

- Maybe you’re thinking about banking: it’s basically impossible for normal people to get a U.S. bank account for a foreign corporation.

- Maybe you’re thinking about rental income and are concerned about the branch profits tax.

There are lots of other reasons to avoid direct ownership of U.S. real estate by a foreign entity.

So you decide that a foreign parent/domestic subsidiary structure is useful. Maybe you want to use a domestic C corporation, maybe a domestic LLC classified as a disregarded entity.

Be careful. By adding another entity, you have added another variable in the tax equation. This means more ways to generate unexpected or unwanted tax results.

What not to do

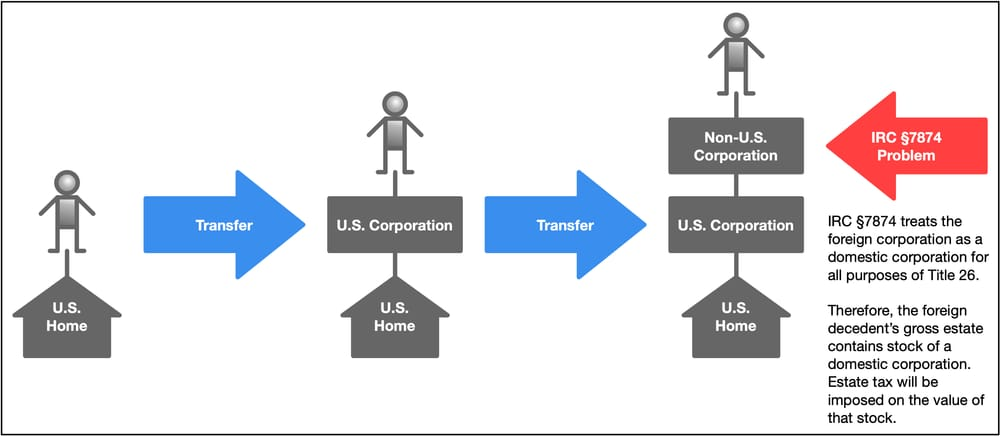

Do not do the instinctively obvious, simple transaction:

- Form a domestic corporation.

- Transfer U.S. real estate to the domestic corporation as a capital contribution.

- Form a foreign corporation.

- Transfer the domestic corporation stock to the foreign corporation as a capital contribution.

There is a footgun, hidden in plain sight in a quiet backwater of the Internal Revenue Code. IRC §7874 will reclassify the foreign corporation to be treated as a domestic corporation.

Now when the nonresident-noncitizen dies, what is in the gross estate? Shares of stock of a domestic (because of IRC §7874) corporation.

Domestic corporation shares are situated in the United States. IRC §2104(a). That means the value of those shares will be included in the deceased nonresident-noncitizen’s gross estate. IRC §2103.

That means that the taxable estate (whatever deductions are allowed) will be greater than zero. And estate tax liability is the result.

Do not follow this process – unless you have a further step beyond it that you will deploy.

The restaurant at the end of the universe

The restaurant at the end of the universe is IRC §7874. It’s not quite the very last section of the Internal Revenue Code, but all of the Code sections beyond it are esoteric and not the concern of mere mortals like us. (Rules that govern the Joint Committee of Taxation, for instance.)

- Income tax rules are in Subtitle A of the Internal Revenue Code.

- Estate and gift tax rules are in Subtitle B.

- IRC §7874 is in Subtitle F – Procedure and Administration.

Why IRC §7874 exists

IRC §7874 is designed to discourage domestic corporations from reorganizing themselves to become foreign corporations.

Why would a corporation do the equivalent of an individual renunciation of U.S. citizenship?

- A domestic corporation is taxable on worldwide income (remember subpart F income and Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income and how that sucks all foreign profit of foreign subsidiaries onto the U.S. parent company’s tax return).

- A foreign corporation is only taxable on its U.S. source income. All foreign-source profits are out of bounds as far as the United States Treasury is concerned.

So a U.S. corporation has a tax incentive to expatriate – just like humans have a tax incentive to renounce U.S. citizenship. After a U.S. corporation becomes a foreign corporation, it will only be taxable on U.S. source income.

How IRC §7874 works

IRC §7874 looks at a domestic corporation (or partnership, but let’s ignore that, shall we?) and asks how much stock a foreign corporation owns after acquiring all of a domestic corporation’s assets.

- If the foreign corporation owns 60% or more of the domestic corporation’s assets, then IRC §7874 creates fake income, called “inversion gain”.

- If the foreign corporation owns 80% or more of the domestic corporation, then the foreign corporation is reclassified to be treated as a domestic corporation for all tax purposes. IRC §7874(b).

How does IRC §7874 do this? By defining “surrogate foreign corporation” as a foreign corporation that acquires – directly or indirectly – substantially all of a domestic corporation’s assets. IRC §7872(a)(2)(B)(i) says:

A foreign corporation shall be treated as a surrogate foreign corporation if . . . the entity completes . . . the direct or indirect acquisition of substantially all of the properties held directly or indirectly by a domestic corporation. . . .

A foreign corporation’s acquisition of stock of a domestic corporation is treated as an indirect acquisition of the domestic corporation’s assets. Reg. §1.7874-2(c)(1)(i).

Therefore, in the transaction I described, the foreign corporation acquired 100% of the stock of the domestic corporation.

- Nonresident individual creates a domestic corporation and transfers U.S. real estate to the corporation as a capital contribution.

- Nonresident individual creates a foreign corporation, and transfers the domestic corporation stock to the foreign corporation as a capital contribution. <– The indirect acquisition of more than 80% of the assets of a domestic corporation occurs here.

- The foreign corporation is a “surrogate foreign corporation.”

The implications of surrogate foreign corporation status? They depend on the percentage ownership of the domestic corporation’s assets after the acquisition.

- Sixty percent or more? There’s “inversion gain” that creates artificial taxable income. That doesn’t matter to us here – we care about estate tax problems.

- Eighty percent or more? Inversion gains don’t matter. Instead, the foreign corporation is treated as a domestic corporation for all purposes of the Internal Revenue Code.

IRC §7874(b) says (emphasis added):

Notwithstanding section 7701(a)(4), a foreign corporation shall be treated for purposes of this title as a domestic corporation if such corporation would be a surrogate foreign corporation if subsection (a)(2) were applied by substituting “80 percent” for “60 percent”.

“This title” refers to Title 26 of the United States Code. That’s the Internal Revenue Code. So for all purposes, the foreign corporation is a domestic corporation. It files Form 1120 instead of Form 1120-F. It is a domestic corporation for employment tax purposes, income tax purposes, and – critically for us – estate tax purposes.

Dreadful.

Bottom line: If you go through the transaction I described in order to create a foreign parent/domestic subsidiary structure, you end up with a domestic parent/domestic subsidiary structure because of IRC §7874.

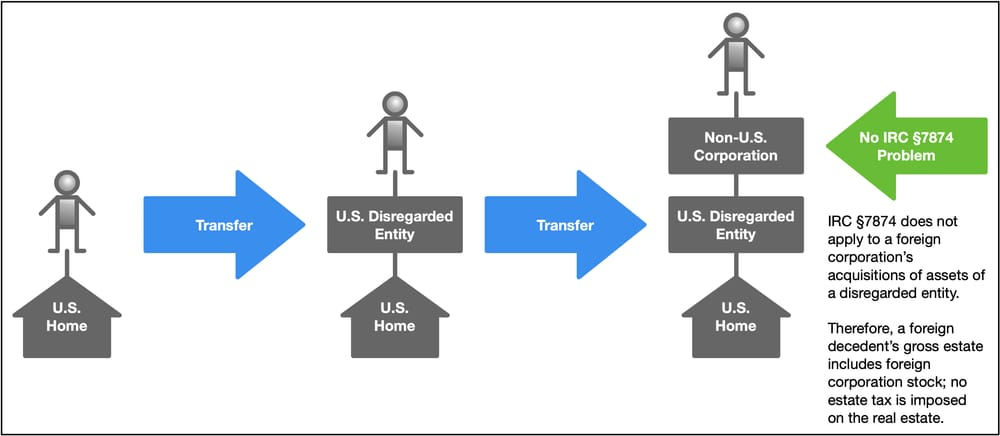

Do this instead

As I said, there are many good reasons to have a domestic entity holding title to the U.S. real estate. Here’s how you can have a domestic entity (making your day-to-day life easier) while achieving estate tax protection: use a domestic LLC (classified as a disregarded entity) instead.

Why does this work?

Simple. IRC §7874 applies to the acquisition of assets by a foreign corporation from two different types of entities: domestic corporations and domestic partnerships. IRC §7874(a)(2)(B)(i). A disregarded entity is not mentioned in IRC §7874, so IRC §7874 does not apply to acquisition of assets from (or membership interests in) disregarded entities.

So your action steps will be:

- Create a domestic LLC.

- The nonresident-noncitizen transfers the U.S. real estate to the LLC.

Since the LLC is a disregarded entity, the nonresident-noncitizen is treated as owning the real estate for U.S. income tax purposes.

- The nonresident-noncitizen transfers the membership interest in the LLC to a foreign corporation.

Now the foreign corporation owns the LLC membership interest and the LLC owns the house. Functionally, this is the same as direct ownership of the U.S. real estate by the foreign corporation.

After the acquisition, the foreign corporation indirectly owns 100% of the LLC’s assets. But the domestic LLC is not a domestic corporation, so IRC §7874(a)(2)(B)(i) cannot redefine the parent foreign corporation as a “surrogate foreign corporation” and cause it to be reclassified as a domestic corporation for tax purposes.

Now, the foreign corporation is classified as a foreign corporation for U.S. estate tax purposes. When the shareholder dies, the gross estate will include nothing. The gross estate only includes assets situated in the United States, and the deceased shareholder owns shares of stock of a foreign corporation, which are considered located outside the United States. The gross estate is zero, therefore estate tax exposure is zero.

Example of how I use this: FIRPTA withholding

I will use holding structures like this to protect against estate tax: foreign corporation owns domestic LLC owns U.S. real estate. It’s imperfect but frequently adequate. It provides estate tax protection, at the cost of income tax brain damage.

Shortly before a planned sale of the U.S. real estate, I will have the domestic LLC make a check-the-box election to be classified as a domestic corporation. When the sale occurs, the seller is a domestic C corporation, therefore FIRPTA withholding is not imposed.

What if I’m wrong?

Does IRC §7874 somehow (through the magic of the step transaction doctrine, perhaps?) apply in this situation to cause the foreign parent corporation to be reclassified as a domestic corporation? I don’t care.

For income tax purposes, all of the gain built into the real estate is going to be recognized shortly in a real sale to a real buyer. If I accidentally trigger gain through some sort of paper transaction, I don’t care. Whether it’s a paper transaction-triggered gain recognition or a real sale, the income tax liability will be created.

For estate tax purposes, even if IRC §7874 causes the foreign parent corporation to be treated as a domestic corporation, I don’t care. It’s a matter of a month or so between the effective date of the check the box election and the actual sale of the real estate. I figure we can get the real estate sold and the whole corporate structure liquidated before my client dies. 🙂

Yes of course there are a lot of collateral questions to deal with. But during the holding period for the real estate, the foreign corporation acts as a firewall against estate tax.

Epilogue

Here’s some stuff coming up on my calendar. I hope you participate in the international tax extravaganza coming your way.

CalCPA International Tax Conference Online

On January 31, 2024 I will be doing a one-hour presentation for the CalCPA International Tax Conference which is totally online again this year. (Hopefully next year we can do a real-life in-person conference). It will be about FIRPTA topics. I’ll keep you posted.

Next Year’s International Tax Lunch Series

Also, in the upcoming year I will be doing a five-episode series for the International Tax Lunch on FIRPTA-related topics (all about foreign investment in U.S. real estate) and another five-episode series on foreign trusts. We are still nailing down the precise topics and schedule with CalCPA.

CFC Reorg Workshop

On January 27, 2024 I will be doing the next episode in the Form 5471 series. It will be about reorganizations, liquidations, etc. of CFCs. That is a one-hour overview of the topic, so will cannot go as deeply as I would like.

In order to test some theories that I have, I will be doing a separate deep dive (probably 2 hours, maybe 3) on one of the topics related to CFC reorgs, probably the week after the overview webcast on January 27, 2024.

The topic will likely be a detailed review of an IRC §368 nonrecognition reorganization of a CFC. What are the rules, how does it work, what are the compliance requirements, what does the 5471 look like, what does the 1120 look like?

The workshop will cost money. I want to deliver deep, hardcore international tax knowledge to you. The theory I’m testing: will people pay for it? Preparation for a typical session like this takes me 50 – 60 hours. Is it worth my while? Let’s see what the market says.

If you’re interested in participating in the CFC reorg workshop send me an email. I’ll make a little mailing list and keep you updated as I nail down the details and price.

Oh. And one more thing.

Thanks for subscribing. I get a great deal of pleasure banging these newsletters out, and I enjoy hearing from you. International tax practitioners are few and far between, and sometimes we get a bit lonely. I appreciate the connections I make with people who read what I write.

So email me and say hi. Be my friend.

All the best,

Phil.